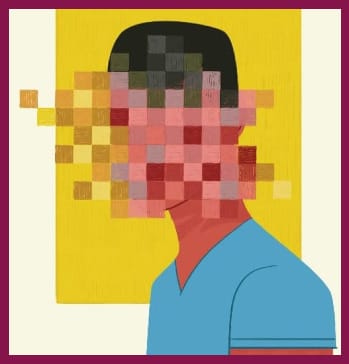

The Body as a Password: The Cost of Face ID

Convenience is costing people their freedom. Research shows that features like Face ID and fingerprints enable violent, forced phone access by police and authorities, writes Afsaneh Rigot.

The link between biometric locks and physical violence has been one of the starkest findings from our research on Queer Resistance to Digital Oppression. Between 2019 and 2024, the report, published with ARTICLE 19, examined tech-facilitated harms against LGBTQ people in the Middle East and North Africa, where their identity is often criminalized. Every participant who was detained by authorities, and had biometrics enabled, said they were violently forced to unlock their phone. As one Lebanese participant described:

“Immediately, when we arrived at the precinct I was handcuffed. He kicked me to the floor and asked me to open it… He came close to me with the phone in his hand and forced me to place my fingerprint… They then dove deep into my phone.”

Biometric authentication locks on devices are features like Face ID, fingerprints, and other body-based locks we see on our every day tools: from opening our phones to accessing apps. These features are a venue for pure convenience for many, but their fast cultural adoption overshadows dark safety and cultural risks.

Since our 2024 research, we have seen similar patterns globally, including against activists, journalists, and migrants in the US, Israel, Mexico, and Iran. An advocate working with detained Iranian protestors said:

“They handcuff them and put their finger on the phone. Even if they cover their face, someone holds their neck and presses their face to the phone for Face ID. This is common.”

Each case has the same pattern. What we see in the research is a shift – not only of how police forcefully manipulate the body for guaranteed access, but that with these biometric locks, the ability to resist becomes close to none. The cost of forced access is devastating beyond the wounds it leaves on people’s bodies, leading to years of imprisonment and exposure of entire networks of friends and family. Data that is uncovered – such as political materials, protest photos, or evidence of queerness or another criminalized identity – is accessed through forced unlocking and has led to severe sentencing.

Those using only passcodes retained some ability to refuse, delay, or obscure access. Many still faced violence, but they recognized that full exposure of their devices – and the risk to their communities – was the ultimate threat. Choosing resistance, even at great personal cost, sometimes led to lesser charges. This route does not exist when abusive authorities see your body as the key.

The expansion of this feature has also enhanced loopholes against privacy. In the US, passcodes (as knowledge) are generally protected as "testimonial" information by the Fifth Amendment, meaning authorities typically cannot compel a person to verbally disclose it. Biometrics, on the other hand, are treated as “non-testimonial” physical evidence. This distinction allows authorities to compel biometric unlocking – holding it in front of your face or grabbing your hands. This loophole disproportionately targets immigrants, people of color, and activists. Even in other global jurisdictions, the weakest form of digital security is against government access to devices – legally or extra-judicially. When the body is the password, and power can compel the body, what is at risk dramatically expands and defenses abate.

Regardless, tech companies still frame them as the inevitable, ultra-secure future of access control. By 2022, biometrics were enabled on over 81% of smartphones globally. Apple claims the probability of a random person unlocking an iPhone using Face ID is less than one in a million and even promotes it in its Personal Safety User Guide as “an extra layer of security.” In May of this year, Microsoft recently shifted by making all new accounts passwordless by default, promoting biometrics-based passkeys for increased “usability and security.”

But the question remains: security for whom, and from what? As social, legal, and political realities shift, more people are being criminalized or surveilled – and they face the greatest risks. Authoritarianism is rising, and these systems favor biometric locks too. The normalization of biometrics as the ultimate mark of safety has created dangers that extend beyond technology: into culture, law, and power, expanding and legitimizing its use across more systems as the most “secure” and “authenticated” option.

Many will frame variations as very secure: The problem is not only where biometric data reside, but what their design assumes. Local storage and data minimization, as practiced by Apple, or public key cryptography of passkeys like Microsoft, may reduce certain risks but offer no protection against highest risk coercion.

When WhatsApp launched chat-lock and hide features in 2023, developed with our team based on our research in MENA, it was a great win. The feature is based on scenarios of device searches and interrogations. It provides a secure and invisible folder for the most sensitive chats and is only made visible by a secret passcode. It is a very stealthy harm reduction feature based on real, lived risks of the most vulnerable. However, the initial version required Face ID or fingerprints. This was seen as a safety upgrade that would add an extra layer of security – yet without our consultation. Consequently, it excluded the very people who needed it most but could not risk using biometrics – the very people who originated the idea. After further working with our team and responding to feedback, WhatsApp tweaked the design so that biometrics is no longer a requirement for this feature, but an option. We continue to work with them to improve the feature based on need.

The inclusion of biometrics framed as extra security was part of a pattern. Major platforms – including Apple and numerous banking apps – increasingly promoted or required biometrics for routine access to security features like app or folder locks from 2023-2025. Ironically these features went mainstream only after years of work on harm reduction changes by teams like ours, rooted in the experiences of the most over-policed. These additions were framed as extra-secure, and non-bypassable methods for routine access, but were in fact making them less safe and private. In some cases, it became the only way to access privacy tools. The rationale focused narrowly on theft or hacking, ignoring the physical and systemic threats many face daily, further normalizing invasive tech.

The Promise of 'Convenience'

Companies, like Apple, normalize body-based access as the ultimate layer of privacy for safety and convenience. But it has deep cultural consequences. Though many security experts are familiar with these companies' existing privacy concerns, most everyday people may see them as the standard for privacy. Their promise of convenience and privacy on personal devices has now trained many to see the act of unlocking phones with our faces and hands as routine. It has helped to make scanning our bodies feel normal, or even as a sign of security itself. This trend will be difficult to reverse, particularly in an era of global police overreach.

It has gone from “convenience” into an expectation. That expectation now runs through airports, supermarkets, borders, and even the UN. Once we accept scanning of our physical attributes as normal and trusted, few will question it when it becomes mandatory for travel or public services. Today, we see its power: US Immigration and Customs Enforcement calls fingerprints and facial scans its most impactful tools for tracking, detaining, and deporting migrants – and continues to expand its reliance on them.

By framing and embedding biometric unlocks into "safety" tools, major platforms with established privacy reputations are reinforcing a dangerous normalization: the acceptance of constant bodily data capture. This commercial endorsement leverages user trust to legitimize biometrics as the most secure and convenient default, thereby entrenching biometric dependence in how we interact with it everyday. Consequently, this seamless corporate integration, and making the scanning of our faces daily seem innocent, implicitly extends to the surveillance state. It makes the constant monitoring and potential compulsion of our personal data normalized – directly countering decades of privacy advocacy.

To push back we need both narrative and technical shifts. Framing a feature as convenience could be OK and accurate, but we must not frame it as one for safety and privacy. It sets a bad cultural precedent and is not reflective of our realities. People should have a true understanding of what they trade for convenience. Biometric authentication should also never be the default or required, especially for privacy or safety features. It must remain optional, with clear alternatives – and not one that is heavily promoted under false promises. Some users may always choose convenience while others unwittingly trust the rhetoric about biometrics being the most secure option. Real safety is built on honest design that is tested not just for usability, but for resistance to coercion by abusive states, police, border agents, and others. Security that ignores these realities fails us all.

The normalization of biometric authentication has already reshaped how we accept surveillance and introduced new violence. Reclaiming privacy means challenging this drift. The future of safety cannot depend on surrendering our bodies as passwords.

De|Center in the World at MozFest

The De|Center continues to do research into state abuse of biometric locks and pushes technologists to think of how to design for convenience without risking real, lived safety around the world. We look forward to collaborating with many of you; including our participants at the upcoming Mozilla Festival on biometrics.

If you’re at Mozfest,our panel “FaceID(ictator): Authoritarians Love Biometrics. We Don’t.” will be on Sunday Nov. 9, 2:45-3:45 GMT+1

And we will be around for the whole weekend! Reach out to contact@de-center.net if you want to connect.